Folding My Mother In

- Summer Lewis

- Apr 3, 2024

- 7 min read

A terrifying hemorrhage leaves a girl with – and without – her mother. Decades later, art bridges the gap.

My mother told me that a mean old rooster used to chase her around the farmyard, so her father chopped off its head — but it still ran around headless. I was but a girl when she told me this story and I didn’t like thinking about a bloody headless rooster.

What scared me the most though, was the idea that my mother could be afraid. I counted on her for bravery.

Occasionally, I was allowed to go through an old trunk of her things from childhood. I found a scrapbook from high school where she had cut and pasted magazine pictures of the rooms of her dream home. When I compared these pictures to our house, I knew she had not realized her dreams. I also found a small, sepia-toned photograph of her sitting bareback on a horse when she was a young child. She was barefoot and her dress was ragged and dirty. She had grown up poor in Kansas during the Dust Bowl. Her father was a bootlegger, and the story is he was murdered by his gang.

My mother was quiet and soft spoken. I had to watch her face for signs of how she felt about things. I knew that when her eyes flashed and she pursed her lips, she disapproved — but wasn’t saying the words. I was vigilant. Those eyes and lips were my barometer for good and evil.

When I was 12, my mother had a cerebral hemorrhage. She barely survived brain surgery. When my father brought her home, she was not the mother I knew. Eventually, I realized that she was gone. This was a problem because there was a body walking around that looked like her. People congratulated me on having her back, but no one was saying, “I’m sorry your mother came back a zombie.”

The day before her surgery, my three younger siblings and I visited our mother at the hospital. She came down to the lobby in a wheelchair. I remember she looked especially beautiful – a new hairdo, make-up, red lips, and pink cheeks that matched her paisley pink robe.

No one told us that this might be the last time we would see her.

My mother knew, of course. She knew she was coming to say goodbye to us. She came looking her best, so we would have that one last memory of her. She never let on, even though she must have been wracked by fear and grief.

Now at 68, myself a mother and a grandmother, I know that on that impossible day, she carried the great weight of a mother’s love with impossible bravery.

In a photo, taken just months before my mother fell ill, my family poses in front of our van before setting out on a camping trip. My parents stand protectively on either side of their 3 younger children. I stand next to my mother, outside of this protected group. As the eldest child, I aligned myself with the adults. I became a protector trainee when the birth of my first sibling made me a “big sister.” Today you would say I was parentified. You would also say I was my mother’s “mini-me.” In the photo, we are dressed alike and standing alike. Our hands are clasped in front of us in the same way – the left hand lays on top of the right.

The 10-year-old sister in the photo and I are now in our 60s. We try to talk about our childhood, but we draw a blank for great swaths of time. I tell her trauma causes this frustrating amnesia. Back then, we were children navigating our new scary world without a guide. It was the era of “children should be seen and not heard.” Our parents belonged to the “Silent Generation,” so no one was talking to or explaining things to children. We didn’t know we could ask.

The day of my mother’s cerebral hemorrhage is still a vivid memory.

My father was out of town. It was late afternoon. I knew Mom would need help with dinner soon. I was in my room reading a book. She yelled my name. I ignored her. She yelled my name again. I ignored her. The third time she yelled, I threw the book down in a huff and begrudgingly went to see what she wanted. I found her lying on the couch holding her head, complaining of a headache, and telling me to call her doctor.

I had no idea how to carry out this request. I was not the caller-of-doctors. She was. Was I even supposed to be using the phone?

She told me his name, and I flipped anxiously back and forth through the telephone book. In my panic, I had forgotten the alphabet. The nurse I finally reached heard only a child saying her mother had a headache. She told me to give her an aspirin and hung up.

Not knowing what to do next, I laid my head down next to my mother. She whispered to me to go get our neighbors, so I ran as fast as I could and brought them back. The man picked her up in his arms, carried her out to the car and drove her to the hospital.

Until I was much older, I carried the terrible secret of my own guilt. If I had not ignored her, she would have been saved. If I had not forgotten the alphabet and found the doctor’s name faster, she would have been saved. If I had known the right words to use with the nurse, she would have been saved.

After the surgery, we were hopeful, but the person we knew as our mother never returned.

Sometimes things got scary. One night, I woke to bright lights, loud voices and the sound of gurney wheels clicking down the hall. Uniformed men with walkie-talkies shooed me back to my room. The next morning, I learned that an ambulance had taken my mother back to the hospital for a few days. She also often went missing. Once she got on a bus and was gone for days. My dad would panic, call the police, we would be questioned, and a search would be made.

When the rich out-of-state relatives arrived, I knew things were serious. It was decided that the three younger children would spend the summer with them. Though I knew a trip to my relatives would mean swimming, horses, amusement parks, and maybe even school shopping, I chose to stay at home with my father. I didn’t want to leave him alone. I was turning 13 that summer. I remember thinking it was time for me to grow up.

With that, my adolescence began its sham existence.

If my mother was a zombie, I was a ghost. I had yet to fill in the spaces in me from her absence. The person I had counted on for bravery was helpless and incompetent. Looking at her was like staring into a glaring spotlight revealing everything I secretly believed I was too. Things I didn’t want other people to see. Hatred and anger girded me to meet the daily shock of my life. With no way to grieve the loss of someone still living and no escape from my pain, I began cutting my mother out of my life.

I spent most of my teens with my girlfriends. They all hated their mothers. I did too, but I knew it was different. I could have taken a darker road, but I didn’t want to rock my family’s already sinking ship. I studied hard, played in the marching band, and orchestra. I got good grades, scholarships and went to college. I did most of this on my own. While my friends were getting sent home from school because their skirts were too short, I had no leeway for rebellion. I was busy parenting myself.

Eventually, however, the ticking time-bomb of repression inside imploded. People, including my father, helped me. From there I began a lifelong journey of self-exploration and healing that led me to art.

A few years ago, I decided to make a collage portrait of my mother. Art never fails to peel back layers in my psyche, surprising and enlightening me. I knew that there was more to explore in my relationship with her.

Not surprisingly, the portrait is very child-like. I’ve granted the wishes from my mother’s dream book. I’ve broken the neck of the villainous old rooster and hung its head triumphantly around her neck. I’ve adorned her with hearts and rhinestones as proof of my love. I’ve released the words from her lips that she never spoke, and they appear as alphabet blocks.

The portrait channels the child who found out her mother could be afraid and wants to make it all better, the teenager who wants to atone for her bad behavior, and the daughter, now an adult, who wants to reclaim their relationship, tell her mother’s story of bravery, and take strength from it for her own life.

But, as these things go, my mother’s journey has always been a part of my own. As I age, we become more alike. I am often inept, confused, and forgetful. As I cultivate acceptance and compassion for my aging self, I can offer this same compassion to my mother’s memory.

Am I living now for her or for me? The line is blurred. I do know that fear has been vanquished, love has triumphed, and the rooster is beginning to crow out loud in my voice and with my own words. Finally, somebody is talking.

I am folding my mother back into my body.

Artist Summer Lewis uses visual art, writing and poetry co-creatively to accomplish one thing – to tell a good and true story. She was a digital pioneer, launching a social media marketing business in 2008. In 2012 she began a 7 year “walkabout” of Oregon, working remotely and blogging from the road. She lives and creates in Ashland, Oregon.

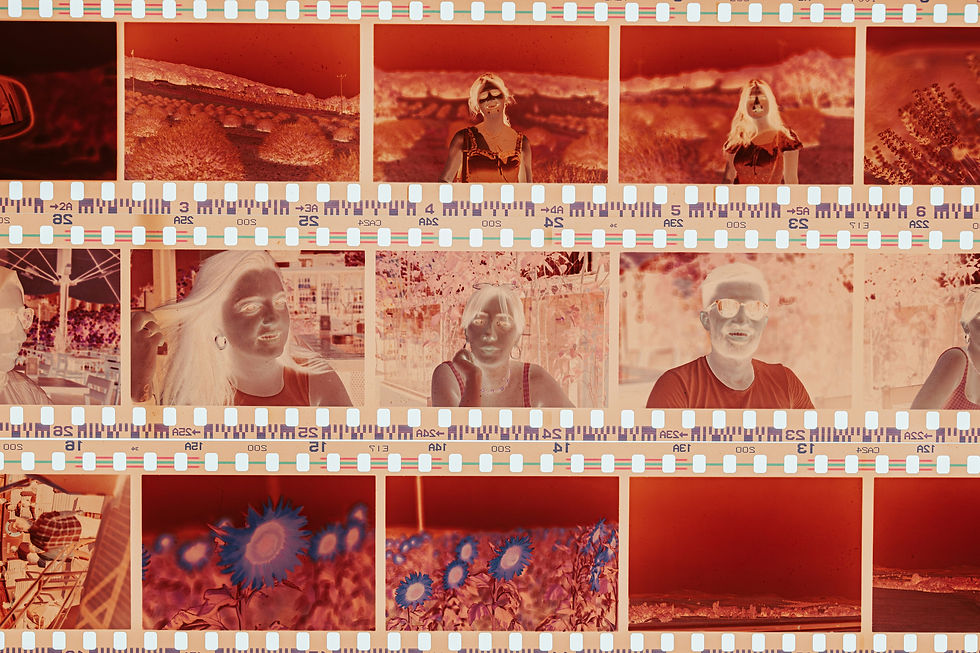

Image Credits:

Horizontal negatives by Ahmed

Vertical negatives by Caleb Minear

Collage courtesy of Summer Lewis

Beautiful story of your own growth through the trauma of your mother's illness.

I found this touching story profound in content and so beautifully written. Thank you for sharing

Those last nine words .... shamanic!